Return to kits for sale

By Alan Bussie Google+ profile

My sincere thanks to Art Cox. Without him this biography would not have been possible.

Box artwork is a major part of model kit collecting. In many cases, the illustration is more important than the contents! The most colorful and desirable kits are from 1953 to the early 1960s, which is considered the ‘Golden Age’ of model kit artwork. During this time, easy-to-assemble kits with dramatic box tops swept aside all pastimes and became the #1 hobby of teenage boys in America until the 1970s.

Jim and Aurora’s longest continuously used box art – the classic Fokker D-VII from 1956

Model kits were not always popular and colorful. From 1910 to the 1930s, boxes were usually very plain, stating the company name and perhaps a simply drawn scene in one color. By the 1930s, producers of wood and tissue flying kits were creating hobby empires, and packaging took on more color but still lacked flair.

More often the artwork was generic. For example, Comet and Megow often used the exact same box art on every kit. The name of the model inside was stamped on the end flaps. By the late 1930s, mid-1940s, simple illustrations of the actual kit inside were being used, but few were in color. More expensive kits featured better illustrations, but tended to stress the authentic appearance of the model.

Megow and Comet generic kit boxes from the 1930s

Berkeley stick-and-tissue Stuka Kit from the 1940s

This was the situation when Hawk and Varney introduced the first US plastic kits in 1946. Hawk used typical one or two color illustrations. Varney produced some of the very first eye-catching kit artwork, but sales failed due to improper marketing and the kits were quickly discontinued. Plastic kits did not sell well until the Gowland/Revell Highway Pioneers were launched with proper marketing in 1953. Other plastic kit manufacturers followed quickly, but with the same simple art style as the Highway Pioneers.

Hawk first issue Curtiss Racer from 1946 and Gowland/Revell Highway Pioneers generic box

Aurora, led by company founders Abe Shikes, Joseph Giammarino and salesman John Cuomo, were the savviest marketers. They knew something must to be done to attract young buyers to this new product. That ‘something’ would be the artwork of Jim Cox. Although kit buyers did not know his name, Jim would become synonymous with Aurora during the years of explosive growth. But Jim was more than a box artist. His training and talent lead to a highly successful five-decade journey from commercial art to fine art, scrimshaw, jewelry engraving and more.

Early Years

James Pettit Cox was born in Bridgeton, N.J. on January 2, 1910. He showed a strong interest in drawing, which was greatly influenced by his mother, Emma Cox. From what we know, Emma enjoyed drawing at an early age. She received her first formal instruction at the South Jersey Institute, a private secondary school in Bridgeton. Later, in the 1890s, she studied at the School of Design for Women in Philadelphia, which was founded in 1848 as the first woman’s visual arts school in the United States. The faculty included many notables such as Robert Henri and Emily Sartain. It is very likely that Emma passed the influence of these artists to her son.

School of Design for Women circa 1863 (internet)

Formal Studies

There was never a more exciting time to be a commercial artist or one in training, and it was fortunate that James was raised near Philadelphia. From the Post-Civil War Period to the first quarter of the 20th century, Philadelphia was the national center for fine art with a wide selection of schools offering studies from modern European movements to the rise of the famed Brandywine River School of Illustration. After graduating from public high school in 1928, Jim enrolled in the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art. This school was founded in 1876 and can trace it roots to one of the oldest universities dedicated to the arts in the United States. Many influential artists, illustrators and instructors contributed to the atmosphere at the Museum School – William Merrit Chase, Joseph Pennell, Robert Henri, and impressionist painter Daniel Garber- just to name a few. One of his instructors at the school was the well known illustrator Thornton Oakley. Oakley had been a student of Howard Pyle, contemporary with N.C. Wyeth at the old Mill in Chadds Ford, now home of the Brandywine River Museum. Jim’s early work combined influences of this school and the Academy of Fine Art (Philadelphia), which he also attended.

Brandywine Museum Today (internet)

Early Career and PLS

When he finished with his studies in the 1930s, Jim worked as a WPA (Works Progress Administration) art instructor and did freelance commercial artwork. Some of this work included very colorful (and now-collectible) food and canning labels. During his spare time he pursued creative drawing and painted scenes and buildings in and around Bridgeton, N.J.

Monarch Canning Label circa 1940s (artist unknown)

Fruit Crate Label (artist unknown)

His professional career began to develop in the 1940s with freelance and commercial work locally and from his Philadelphia office. By the late 1940s he was designing print work for the Printing and Lithographing Service Company (PLS) in Fairton, N.J. and was affiliated with an advertising agency in Philadelphia. At the latter, Jim and two other artists did black and white ink drawings for newspaper advertising. The art work had to be executed quickly and with eye-catching appeal. It was usually only used once. This type of work was done on tight deadlines. Jim quickly improved his skills, and soon landed his own accounts.

But it was through PLS that Jim would achieve renown in the modeling industry. PLS was founded prior to 1950 by George T. Burt and a partner. Their first work was with the well-known canning and frozen food maker, Seabrook Farms. PLS continued to expand and in 1951 Jim accepted full-time employment as the in-house artist. He no longer had to work in the ‘big city’ and the daily commute was eliminated.

Beautiful Seabrook brochure cover and insert, artist unknown (click to enlarge)

Enter Aurora

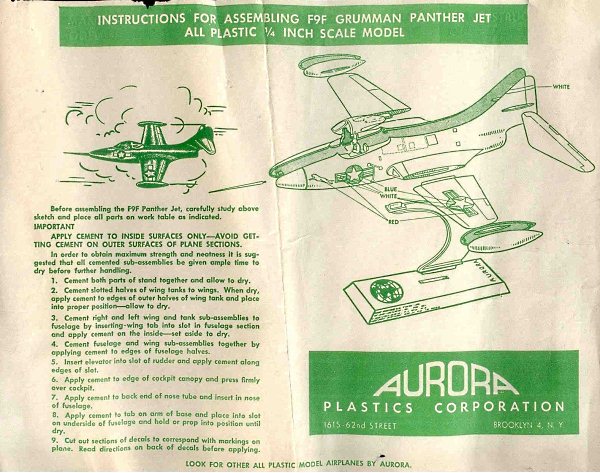

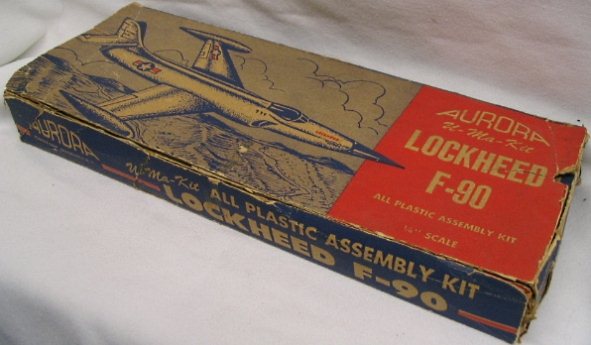

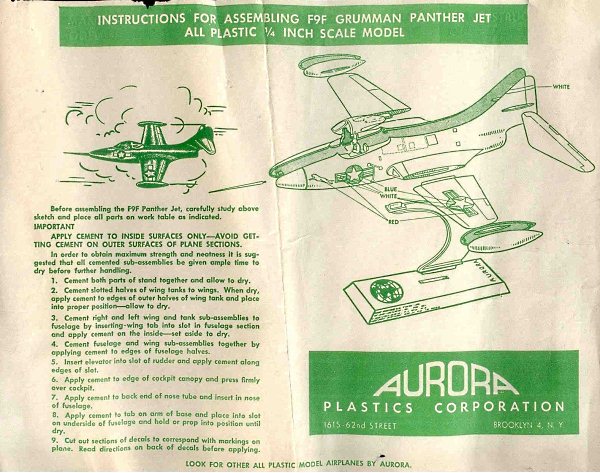

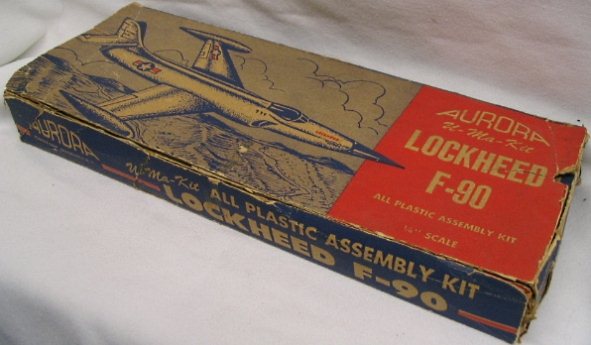

In 1952, the young Aurora Plastics Company approached Burt at PLS about creating instruction sheets. The project was handed to Jim, whose work on the newspaper illustrations had prepared him perfectly. He drew the first Aurora instruction sheets for the F9F and the F-90. From the small drawings on the F9F sheet, it is almost certain that he did the ‘flip top’ box artwork also. The precise, clean exploded parts diagrams impressed the Aurora team – so much so that Jim did almost all of Aurora’s instructions well into the 1970s.

Jim Cox’s first instruction sheet, the Aurora ‘flip top’ F9F

Aurora F9F Panther first issue ‘flip box’

Aurora’s second kit, the F-90, artwork also obviously done by Jim Cox

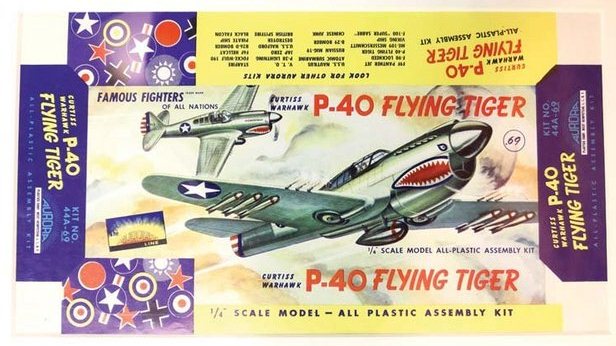

The F-90 and F9F were issued in very thin, inexpensive one-piece folded boxes. They were easily damaged, and did not stand out from other products on the shelf. Aurora immediately chose to take a much more expensive approach to marketing – a heavier, two-piece cardboard box (tray and top) with the top held together by a lithograph ‘slick’ glued into place. This was no small decision. In these days, printing was expensive, and it was said that the ‘box costs more than the contents’ in these early years. The tiny Gowland/Revell Highway Pioneers used this sturdy box, but with generic artwork. Aurora would take it to the next level. The result was the eye-popping artwork of the ‘Brooklyn 8’ in 1953. Sales were fantastic, and Aurora knew they had the right combination. Jim did the new artwork for old F-90 and F9F reissues as well. Soon they were a major client of PLS and Jim was kept busy doing four color illustrations and black and white instructions for Aurora’s rapidly increasing kit line.

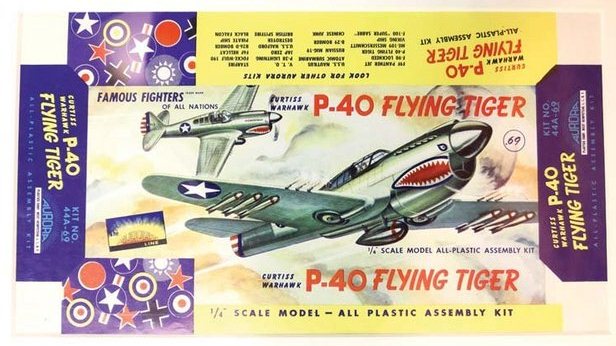

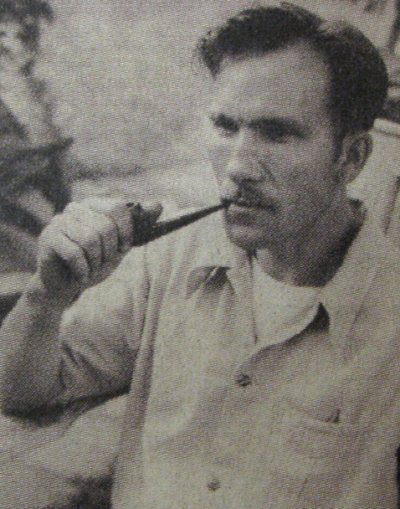

Lithograph ‘slick’ on heavy paper of Jim Cox’s ‘Brooklyn’ P-40 artwork. The slick was glued around a cut and folded heavy cardboard to create a box

The famous ‘Brooklyn 8’ in the Aurora Line. (click to enlarge)

Model companies, like all manufacturers, had specific methods for handling artwork. For example, at Revell and Hawk, sketches were made of proposed artwork. After review, the artist would do two or more rough color drawing or paintings (“comps”) that were a step above a sketch. The company would select a comp and request certain changes to it. The artist would then create the final painting or ‘finish’ artwork, which was ready for publication after the logo and text was added. Although this took longer, this system controlled artistic costs. In the era before computers, talented commercial artists were in high demand and made an excellent living.

From seeing Jim’s original compositions for Aurora, it became clear that their process for developing box art was not like most other model companies. For Aurora, Jim would first create sketches. Aurora would choose one or more sketches and make recommendations. Evidently, no comp artwork was done. Jim would then directly paint one, or surprisingly, multiple pieces of finished artwork. What happened next is more of a puzzle. In some cases, the single finished piece was never used on the box; Aurora simply changed their minds. Sometimes it would appear in brochures or a catalog. When multiple finished pieces were painted, Aurora would choose one for the box slick. The other(s) were either never used for anything else, or they appeared in other advertising. Below is a sampling of his original Aurora artwork and what it was used for-

(Click to Enlarge)

Jim’s pencil study and finish artwork for the Nieuport 11 Fighter, about 1955.

This artwork was not used on a box but was used on an Aurora sales brochure.

Both pieces of finish artwork for the Aurora B-29; only the lower one was used (click to enlarge)

Two pieces of finish artwork for the B-26; only the one on the right was used (click to enlarge)

Finish artwork for the P-40 ‘Train’ and Brooklyn issue (click to enlarge)

Finish art for one of at least three Cox-painted Aurora Me-109 kits (click to enlarge)

Perhaps the most well-known of Jim’s Aurora box tops are the figure kits (Knights, Three Musketeers, etc), the first three ships (Pirate Ship Black Falcon, Chinese Junk and Viking Ship) and the World War I aircraft series in 1/48. This latter was launched in 1956, and many were still in production until Aurora closed in 1976. Most of the artwork was modified as the Aurora logo changed. In the 1960s many paintings were replaced with more modern art from Jo Kotula. But one illustration was clearly a favorite of the Aurora staff – The Fokker DVII. This was possibly the longest-run box top illustration in Aurora history, lasting from 1956 until the early 1970s when it was finally replaced with a photo of a built model.

The first five of the Aurora WWI series, all done by Jim Cox for the 1956 release (click any to enlarge)

First issue Crusader, Blue and Silver Knights with the original artwork for the 1st release Viking Ship (click any to enlarge)

Jim’s work did not go unnoticed by other kit manufacturers. Soon PLS was doing labels, box slicks, catalogs and instruction sheets for Revell, Pyro (N.J), Bachman (Plasticville), Mantua, Cavalcraft, Advanced Molding Operation and others. Other companies quickly caught on. Monogram added more colorful illustrations to their plastic kits and the Speedee-Bilt line of flying wooden aircraft. Hawk boldly highlighted box art with the ‘Picture Gallery’ series, and shortly after Bill Campbell and Tom Morgan began their colorful, action filled illustrations. By 1955 Revell was commissioning the legendary artwork of the ‘Pre-S’ and ‘S’ kits. A great many more followed – the Golden Age of box art was well underway.

Original artwork done by Jim for Plasticville train accessories and Cavalcraft, and his artwork on the Cavalcraft DR-1 (click any to enlarge)

PLS had other clients, and Jim’s expertise was required in non-model work as well. Other illustrators were eventually recruited for the color work, but even then he continued to make countless model instructions for many companies. His reputation for making detailed step-by-step instructions was second to none, and he took great pride in that.

By the late 1960s, demand for model illustrations had diminished. Manufactures were beginning to stress the ‘authenticity’ of their kits, which usually meant a photo of a professional built model on the box top. Jim continued to make non-model commercial artwork, in addition to completing over forty color illustrations of buildings and scenes along the Cohansey River. Following his retirement from PLS, Jim acquired skill in the ancient art of scrimshaw and engraved jewelry and buttons for collectors. Many of these buttons remain highly prized. Jim Cox died in Bridgeton on March 15, 1993.

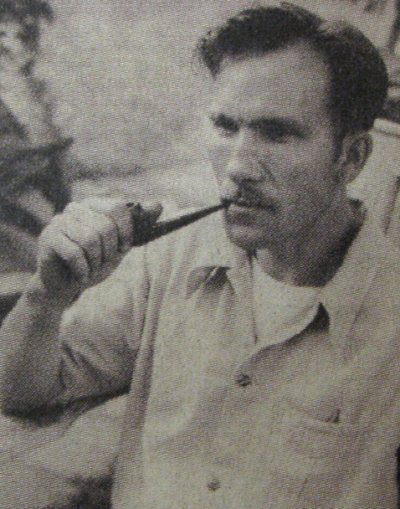

James Pettit Cox 1910 – 1993

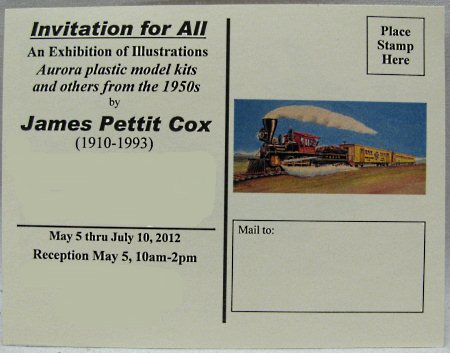

On May 5, 2012, Jim’s son, Arthur Cox, opened “An Exhibition of Illustrations for Aurora Model Kits and Others”. The exhibition was very successful and attracted visitors for over six months.

Front and back of the invitation to the display of Jim Cox’s Artwork

Return to kits for sale